Watch: Liz Kennedy accepts the 2018 AQA Distinguished Achievement Award.

Elizabeth Lapovsky Kennedy

by Kristin Gupta

To honor Dr. Elizabeth (Liz) Lapovsky Kennedy’s life and career is not only an exercise in reflecting on her work, but one of exploring remarkable developments in early interdisciplinary initiatives of gender and sexuality scholarship. A founding leader in both women’s studies and queer anthropology, Kennedy pioneered the development of modern lesbian history and imagined an anthropology that could work towards just and creative futures. These efforts significantly influenced the ways anthropologists have come to do work in LGBTQ communities, helping us see queer archives as profound spaces to think critically about desire, systems of oppression, and interlocking mechanisms of the personal and political.

Kennedy received her Ph.D. in social anthropology from Cambridge University in 1972, producing three documentary films and writing her dissertation on egalitarianism and the Wounaan in the Chocó province of Colombia. She found intense inspiration during fieldwork in ways of being that did not order social organization through strict hierarchies, making Kennedy reflect more broadly on patriarchy in the United States. However, she was conflicted about the politics of research among vulnerable indigenous societies increasingly affected by the reach of global capitalism. Kennedy began teaching at the University of Buffalo in 1971 as a Deganaweda Fellow in American Studies. In search of a more responsible way to use her anthropological training, she became increasingly interested in her students’ experiences in local lesbian bars. Kennedy and her long-term collaborator Madeline Davis then undertook a thirteen-year community endeavor that would become the Buffalo Lesbian Oral History Project.

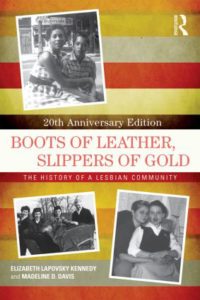

Focused on a working-class lesbian community from the 1930s to the 1950s, Kennedy and Davis’s Buffalo Lesbian Oral History Project explored the lives of a diverse group of women at a time when most historical and contemporary research was centered around middle-class and white lesbians. Their germinal book, Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold: The History of a Lesbian Community (Routledge, 1993), was awarded AQA’s Ruth Benedict Award in 1994 (along with the Jesse Barnard Award and the Lambda Literary Award). It was one of the first community studies of lesbian and gay experience in the United States, shattering the prevailing view that butch-femme ways of being were simply reproductions of heteronormative gender dualisms. Through an exploration of richly detailed histories, their scholarship broke new ground in queer studies by challenging and reshaping approaches to feminism and LGBTQ identity, and highlighted the importance of cultural dynamics and social histories over concepts of fixed or essentialized deviant natures. While Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold quickly became a classic for these contributions during a time when anthropology had not devoted significant attention or resources to studies of homosexuality, the project also was notable for Kennedy’s establishment of rigorous accountability measures within the community. Such methods included returning repeatedly and sharing iterations of the manuscript with interlocutors to ascertain that they were adequately represented and to better capture what she calls “the fleeting and shifting nature of desire.”

This kind of deep commitment to documenting lesbian pasts was also integral to Kennedy’s later work, such as “‘But We Could Never Talk about It’: The Structures of Lesbian Discretion in South Dakota,” an essay in Inventing Lesbian Cultures in America (Beacon, 1996) that looked at upper-class lesbian life in the context of a single individual, Julia Reinstein. Working against simplistic notions of “the closet,” coming out, and the politics of visibility, Kennedy argued that class privilege and family acceptance allowed some lesbians to confidently explore their complex sexualities in private. Other notable works include the co-authored history of women’s studies, Feminist Scholarship: Kindling in the Groves of Academe (University of Illinois Press, 1983), the edited collection Women’s Studies for the Future: Foundations, Interrogations, Politics (Rutgers University Press, 2005), and articles like “‘These Natives Can Speak for Themselves: The Development of Gay and Lesbian Community Studies in Anthropology” in Out in Theory: The Emergence of Gay and Lesbian Anthropology (University of Illinois Press, 2002). Kennedy also chose to return to her early ethnography of the Wounaan in a collaborative project with Julie Velasquez Runk to document their language, underlining the strength of feminist and queer methods across disciplines to reveal dynamic ways of understanding power dynamics within indigenous societies (“Enriching Indigenous Knowledge Scholarship via Collaborative Methodologies: Beyond The High Tide’s Few Hours” published in Ecology and Society, 2014).

In addition to her many and invaluable scholarly contributions, Dr. Kennedy has also played a significant role in legitimizing the study of gender, beginning at a time when many universities attempted to stifle alternative educational enterprises fueled by student movements. Notably, she helped found the Women’s Studies College at SUNY Buffalo, one of the first Women’s Studies institutions in the United States, teaching there for twenty-eight years. In 1998, she moved to the University of Arizona, to build their Gender & Women’s Studies doctoral program. Listening to the many accounts of those she mentored (both in and out of anthropology), Kennedy’s teaching and institution-building emerged as a critical part of her push for social and political change through experimental and transformational ways of learning that provoked the limits of the university. As she put it much more simply and humbly in conversation, “I was stubborn, and it served me well.” Today, Elizabeth Kennedy stands out as the definition of a groundbreaking scholar, uniting concern for gender, race, class, sexuality, and nation in her writing and professional praxis. Perhaps most importantly, she is someone whose legacy continues to remind us of the importance of rebellion, resistance, and revolutionary spirit in our current times.

Kristin Gupta had the chance to sit down with Liz Kennedy in November of 2018 for a brief conversation about queering language, lesbian and queer history, the women’s movement, and the importance of feminist rage.

KG: What brought you to queer anthropology?

LK: There were two things that pushed me in that direction. The first was lesbian studies, which aren’t necessarily queer (or at least, weren’t at the time). When I realized the difficulty of doing fieldwork in Colombia with indigenous people, where the power differential was so great… I couldn’t figure out how to disrupt those relations so easily, so I thought to do a study focused on the United States. I was listening to my graduate students talk about going out to the lesbian bars (in Buffalo), and it seemed like [the women there] had a different culture, and that’s why they wouldn’t talk to [the students]. Sure enough, they did have a different culture. For instance, you couldn’t ask any woman to dance if she was a femme, you had to ask the butch to dance. That’s what got me interested. What were the rules of lesbian life? Of course, that ended up in Boots of Leather.

That work was not necessarily queer though. For example, at the time, I taught lesbian history and the history of sexual communities, not queer history. Then one of my colleagues, Laura Briggs, said to me that I should call it “queer history” after looking over the syllabus. And I said, “No, I don’t think I teach queer history.” She responded, “Believe me, you do!” I then retitled the course and found that just the use of the concept “queer” really helped me explain complicated things to my students. In Boots of Leather,although we use the world lesbian, we try to remind the reader early on that that was not the term people used. They might have called themselves femmes or studs, but lesbian was not the term. We included that in the book and it made people understand that it wasn’t a simple identity they were projecting, but a complex or queer identity, really. “Queer” helps us understand the lack of firm identity. The fleeting nature of desire is so hard to capture in terms like “homosexual,” or even “queer.”

That work was not necessarily queer though. For example, at the time, I taught lesbian history and the history of sexual communities, not queer history. Then one of my colleagues, Laura Briggs, said to me that I should call it “queer history” after looking over the syllabus. And I said, “No, I don’t think I teach queer history.” She responded, “Believe me, you do!” I then retitled the course and found that just the use of the concept “queer” really helped me explain complicated things to my students. In Boots of Leather,although we use the world lesbian, we try to remind the reader early on that that was not the term people used. They might have called themselves femmes or studs, but lesbian was not the term. We included that in the book and it made people understand that it wasn’t a simple identity they were projecting, but a complex or queer identity, really. “Queer” helps us understand the lack of firm identity. The fleeting nature of desire is so hard to capture in terms like “homosexual,” or even “queer.”

KG: Your role in institutional work and legitimizing women’s studies is often lauded and—to be frank—is quite extraordinary. As a graduate student who has already come against a lot of push back against queer and feminist studies, I can only imagine how difficult that work was. What made you pursue it so passionately, on both personal and professional levels?

LK: Oh wow, I don’t know! I was always a stubborn person and very persistent. The two combined really made it so that I was willing stick to proposals, but also I think people found talents that they didn’t know they had through the women’s movement in the 1970s. It is hard for people to imagine today how strong and powerful it was. If you had spoken to me in the 1960s, I would never have said that I would be an activist, a committed activist, and take pleasure from that or think about the ways to disrupt oppressive thinking. But, it turned out that I did have that talent.

I was also creative in thinking about things and creative in taking the offensive, rather than letting myself be pushed into the defensive position. I remember the first time I realized that I was better at this than I ever imagined. To defend the women’s studies college at Buffalo, we had to have a public hearing. This was maybe in 1972. We went out and distributed flyers for the hearing and lo and behold, over 300 people showed up. Women and men. We were all astounded, but I guess what it meant was that there was a movement at that time. We worked on how we were going to present ourselves and I remember coming up with a tidbit about whether the geography department would teach that the world was flat. People were saying that women’s studies was new material and that we shouldn’t be talking about oppression or domination because those were changing ideas. But really, would they expect geographers to still teach that the world is flat? People really liked that analogy. I used to get pleasure from disrupting people’s way of thinking and using words and images to help with that fact. People really loved learning at that time. I loved it too. I guess I was made in the women’s movement!

KG: In your essay, “An Interdisciplinary Career: Crossing Boundaries, Ending with Beginnings” (Feminist Formations, 2012) you wrote about how both positivity for human potential and a deep sadness has kept you going in your work and helped you imagine new projects. What motivates you in the current cultural moment, which is sad, precarious, and frustrating?

LK: There’s so much coverage of refugees and their suffering, the killing of people. I think we have become immune in some ways. People are protecting themselves from it. If they weren’t, how could they live in this world? There is so much displacement and suffering. We’ve gotten used to it. I hate that fact. I think if we are all in touch with our rage, things would be different. We would be storming the castle saying, “Stop this right now!”

KG: Thank you so much for taking the time to talk with me; it has been so nice learning more about your boundary-crossing work and institution-building. My final question is, what is your hope for the future of queer anthropology in particular?

LK: That’s hard to say. I just had the experience of being on a panel in Buffalo, and the audience was amazed at what was taught in the 1970s. The course was set up with topics such as “Who are the women of America?” and had very different women in different positions in it. It wasn’t all middle-class white women, which was what the image was (and sometime continues to be). That’s not what we were teaching though. People were astounded that students in an introductory course read Harry Braverman’s Labor and Monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century (1974), and they were really interested to read it! It would be hard to have introductory students read that now. Everyone wanted to go home and revise their syllabi, because they realized how much neoliberalism has affected what they can teach and their own self-censorship. The university is also requiring many to censor what they’re teaching. It’s interesting, the change in times. So, queer anthropology has grown so much, even in the time since I’ve been away from it. I do hope that it keeps pushing itself and pushing back against systems of oppression.

Kristin Gupta is a graduate student in the Department of Anthropology at Rice University. Her dissertation work focuses on new burial technologies, death activism, and transformations of American deathways prompted by ecological devastation.